By the time you read this, ‘Banned Book Week’ (October 5-11) should have ended.

By the time you read this, ‘Banned Book Week’ (October 5-11) should have ended.

Created in 1982, the event aims to raise awareness about the books that frequently fall prey to censorship laws, primarily within school and library settings. Proponents of ‘Banned Book Week’ call for intellectual freedom.

The sentiment is commendable. It encourages the people in charge to give their citizens the freedom to read whatever they want. Although, if we are being honest, most of us don’t agree with that concept.

I came across an article a few days ago in which the author viciously criticized a school for banning a series of YA novels because of their sexual content. She argued that sex was a natural element of human existence, and banning of sexually explicit fiction in a high school was prudish and backward.

Then she inadvertently revealed that she supported the removal of books with right-wing messaging.

After all, “those books contained problematic ideas with the power to poison young minds”.

Somehow, she was blind to her own double standards, and she is not alone. Most people only oppose book bans when the banned books in question support their beliefs. They won’t hesitate to change their stance once they encounter a book that espouses ideas they hate.

And technically speaking, there’s no such thing as absolute freedom. Every organization has the right to remove from its library any books that oppose the ideas it champions.

Would you criticize a mosque for banning cookbooks with pork recipes? Would you force an abortion clinic to carry anti-abortion literature? For that reason, I rarely lose sleep over book bans.

On a side note, I was tempted to dismiss book bans as a predominantly Western thing, not because I think Africa is more progressive on that issue. However, a brief Google search quickly showed me that some African countries have also banned books in previous years.

What surprised me most was the difference between African and Western book bans. NBC News published an article listing the 15 most banned books in US schools.

It included A Clockwork Orange (Anthony Burgess), Breathless (Jennifer Niven), and A Court of Mist and Fury (Sarah J. Maas). Butler University’s list of commonly banned books is even more curious.

It highlights the novels various governments around the world have challenged and attempted to erase throughout history, including 1984 by George Orwell, The Catcher in the Rye, The Great Gatsby, and One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest by Ken Kesey.

The voices that got them banned attacked these books for their sexually explicit scenes, offensive language, profanity, and references to drugs. These complaints are usually loudest where YA novels are concerned because the genre targets teenagers, and those in power believe that any book that attempts to corrupt young minds is the enemy.

Compare that to Wikipedia’s list of books banned by governments. The few African countries that appear have two common themes, namely, religion and politics.

Kenya, Senegal, Morocco, South Africa, and Tanzania banned The Satanic Verses by Salman Rushdie because it blasphemes Islam (the book is based on the Prophet Muhammad’s life).

Mauritius, on the other hand, accused The Rape of Sita by Lindsay Collen of blaspheming a Hindu Goddess. Morocco banned Notre ami le roi by Gilles Perrault and Le roi predateur by Catherine Graciet and Eric Laurent because they highlighted the political killings and imprisonments the Moroccan government had perpetrated.

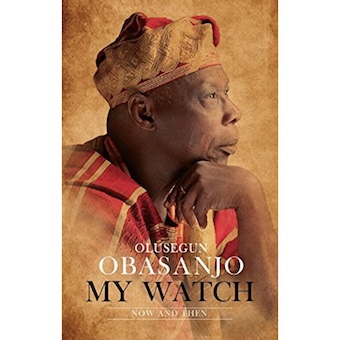

Nigeria banned My Watch by Olusegan Obasanjo for similar reasons. In other words, book bans can provide a fascinating insight into a country’s culture and traditions. They show you what people care about and which subjects dominate their landscape.

katmic200@gmail.com