As Uganda’s political parties sharpen their messages ahead of the 2026 general elections, much of the national conversation is drifting toward familiar ground: economic growth figures, infrastructure pledges, and headline promises tied to Vision 2040 and the ongoing National Development Plan IV.

But far from the campaign rallies and policy conferences in Kampala, a quieter, more grounded political intervention is taking shape in two sub-regions that have long felt excluded from Uganda’s development story.

In Karamoja and West Nile, communities that have spent decades navigating poverty, climate shocks and political neglect have put forward a Citizens’ Manifesto for Inclusive Development and Climate Justice, a document that seeks not applause, but accountability.

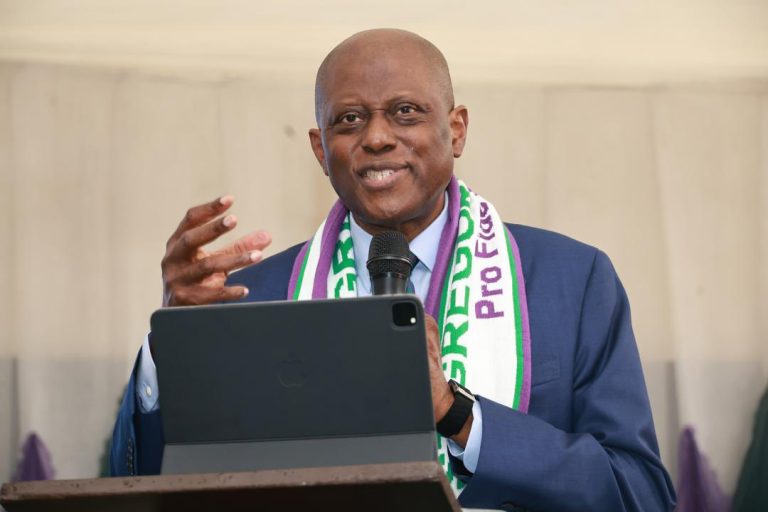

Developed by the Advocates Coalition for Development and Environment (ACODE), the West Nile Development Association (WENDA), and Karamoja Herders of the Horn (KHH), the manifesto aims to influence party platforms, national budgets and post-election priorities by placing lived experience at the centre of policy debate.

At its core, the manifesto is an attempt to reverse the direction of political conversation. Instead of politicians telling communities what development should look like, citizens from Uganda’s most marginalised sub-regions are spelling out what has failed, why it has failed, and what must change.

The inequalities the manifesto describes are stark. Despite decades of national planning, Karamoja and West Nile remain statistical outliers in Uganda’s development profile. Poverty levels in Karamoja exceed 65 per cent, while West Nile stands at around 40 per cent, both far above the national average of 20.3 per cent.

These figures are not presented as abstract numbers, but as the cumulative outcome of structural realities: Karamoja’s arid climate and pastoralist economy, and West Nile’s post-conflict recovery compounded by the pressure of hosting large refugee populations. Basic services remain uneven and, in some places, absent.

In Karamoja, only 59.5 percent of residents live within five kilometres of a health facility. In West Nile, the figure is higher at 87.3 per cent, yet still insufficient for a region with dispersed settlements and rising population pressures.

Education access trails national averages, especially for girls, while electricity penetration remains below 10 per cent in both regions, a figure that underscores how distant industrialization rhetoric can feel on the ground. Layered onto this structural exclusion is the growing weight of climate stress.

Environmental degradation is accelerating across both sub-regions, driven by deforestation, overgrazing, unregulated logging, and prolonged droughts. In West Nile, ecosystems are further strained by the demands placed on land and water by refugee settlements.

The manifesto records accounts of communities being charged up to Shs 20,000 to collect grass near protected areas, a cost that often exceeds the value of the resource itself. Water scarcity has become a defining challenge.

“Only 39 per cent of people in Karamoja have access to clean water, while competition over resources is intensifying in districts where host communities and refugees rely on the same fragile systems.”

These pressures, the manifesto warns, are not only environmental but social, fuelling conflict and deepening vulnerability. Nowhere are these tensions more visible than around conservation areas such as Ajai and Pian Upe wildlife reserves.

Intended to preserve biodiversity, these protected zones have increasingly become flashpoints between state authority and community survival.

“Enforcement measures introduced without meaningful consultation have restricted grazing routes, criminalised subsistence activities like firewood collection, and, in some cases, led to violent confrontations,” the manifesto warns.

The manifesto challenges the idea that conservation and livelihoods must exist in opposition. It notes that more than 40 per cent of Uganda’s cattle milk and 27 per cent of its beef come from Karamoja’s pastoral economy.

Limiting access to dry-season grazing areas, it argues, threatens not only household resilience but national food security, a risk that current policy frameworks have yet to confront honestly. Beyond land and climate, the document paints a sobering picture of social services.

In parts of West Nile, entire sub-counties such as Wandi and Kei lack don’t have a single health facility. Women are reported to give birth on bicycles due to the absence of ambulances. Children study under trees or in classrooms close to collapse, while teacher-to- pupil ratios frequently exceed 1:70.

These are not isolated failures, but patterns that reflect chronic underinvestment and weak local accountability. Governance gaps compound these challenges. Corruption, elite capture and limited citizen participation have eroded trust in public institutions, “while indigenous forest-dependent communities such as the Ik remain largely excluded from decision-making processes that directly affect their land and livelihoods.”

Women and girls bear the heaviest burden. The manifesto details how long walks to unsafe water sources, limited schooling opportunities, early marriage, and exposure to gender-based violence intersect to restrict life chances.

People with disabilities and older citizens are similarly marginalised, often invisible in planning frameworks and service delivery models. Yet the manifesto is not simply a catalogue of grievances.

Its strength lies in its insistence on solutions rooted in community realities. It calls for governance reforms that institutionalise citizen audits and strengthen the participation of women and indigenous groups in planning processes. It argues for climate-resilient infrastructure, including small-scale irrigation, reforestation and drought-tolerant agriculture tailored to local conditions.

On conservation, it proposes legal reforms to mandate community consultation, compensation schemes for crop and livestock losses, and clearly defined grazing corridors within protected areas.

In health and education, it demands the construction of facilities in unserved parishes, the recruitment of frontline workers, expanded water access and reliable emergency transport. Road rehabilitation is framed not as prestige infrastructure, but as a prerequisite for economic integration and market access.

Taken together, these proposals challenge the dominance of top-down development models that have shaped Uganda’s planning culture. The manifesto argues that lasting progress will require locally owned planning, coordinated action across government, civil society and the private sector, and a deliberate shift from short-term humanitarian responses toward long-term resilience.

The political implications are difficult to ignore. As parties prepare their manifestos and candidates craft campaign narratives, the Citizens’ Manifesto raises an uncomfortable question: can Uganda credibly pursue national transformation while entire regions remain structurally excluded?