I have lived outside Uganda for more than half of my life.

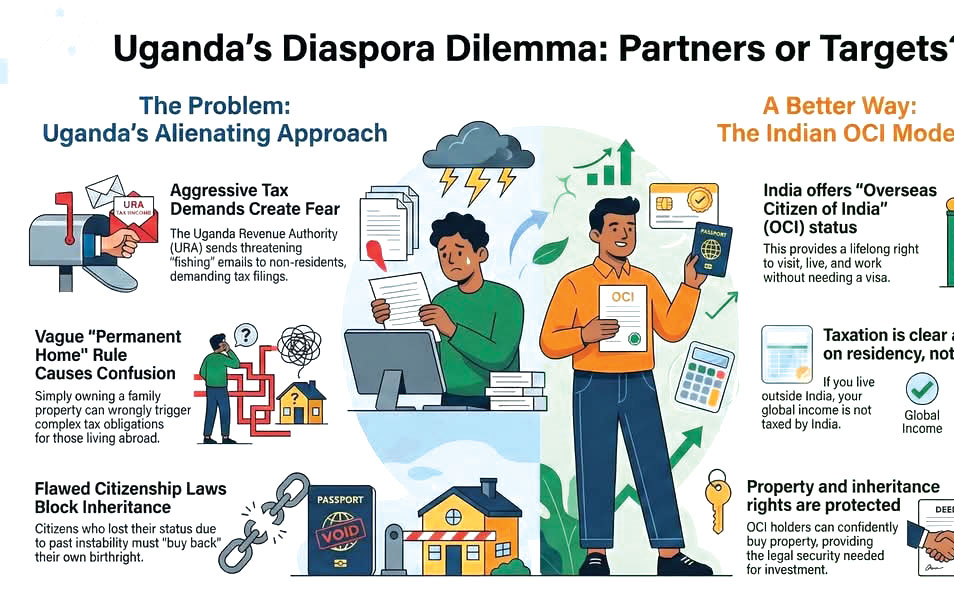

Yet I recently received one of those aggressive “fishing” emails, actually two, on the same day from two different people, at the Uganda Revenue Authority (URA). Never mind I owe no tax.

Complete with threats of penalties, the email demanded I file a provisional income tax return to “avoid accumulation of interest and distress proceedings.”

This approach is not only annoying; it is fundamentally flawed. I travel to Uganda only a few days or weeks a year. I do not qualify as a tax resident. While I own property for family use, I have never lived in it, nor do I consider it a “permanent home.”

Where relevant, rental taxes and local rates are paid. Crucially, I have not taken money out of Uganda in 25 years; on the contrary, like many in the diaspora, I remit a significant amount annually for family support and investment.

Uganda has a large diaspora that contributes significantly to the economy, more than a billion dollars a year in fact. The government is keen to capture more of these earnings. At a recent diaspora gathering I attended, Ugandan ambassadors and officials pleaded for us to remit more money, invest in tourism, and build the nation.

Yet, when it came to time for questions, the officials seemed interested only in a top-down lecture, not in listening to the legitimate concerns of the stakeholders they were trying to woo.

RISK OF ALIENATION

The recent aggressive campaign by the URA targeting the diaspora has the potential to backfire if they do not consult with the main stakeholders. I invest in Uganda primarily for emotional reasons, not strict business returns.

If my holdings become targets for onerous, bureaucratic harassment by URA bots, I, and many others, would have no issue divesting from Uganda entirely. We simply do not have the time to indulge in frivolous, time-wasting processes.

CITIZENSHIP AND PROPERTY RIGHTS: A GREY AREA

There is a misconception that every Ugandan abroad wants dual citizenship or a passport. This is far from the truth. What matters most is access to one’s identity: visa-free travel, “lifetime permanent residency” status, and secure property and inheritance rights. Currently, the dual citizenship law offers limited options.

It effectively disinherits Ugandans (and their foreign-born children) who lost citizenship due to past political instability or conflicts. The only avenue offered is to ‘buy back’ one’s citizenship.

This holds our identity and inheritance hostage, forcing us to pay for a birthright we lost through no fault of our own. Furthermore, the process of reclaiming citizenship is archaic. It requires travel to Uganda to present “proof of being Ugandan,” relying on stamps from local council (LC) officials who cannot possibly know someone who left decades ago.

It ignores verifiable government-issued identity cards, such as expired passports. The system forces reliance on a subjective and often corruptible LC structure rather than solid data.

THE PERMANENT HOME TRAP

This confusion extends to the URA’s definition of tax residency. Under current rules, you are a resident if you have a “permanent home” in Uganda. But what defines a “permanent home”?

If I own a house I don’t live in, for which I already pay stamp duty and local rates, why should that trigger an income tax filing obligation? Tax residency laws should not be used to create onerous paperwork for people who do not derive income from those assets.

If the URA insists on chasing pennies from the diaspora using vague criteria, they will discourage the very investment the government claims to want.

A BETTER MODEL: THE INDIAN EXAMPLE

Uganda does not need to reinvent the wheel. India, which also has a massive diaspora, manages this balance much more effectively by distinguishing between citizenship and residency rights.

Indian citizens are either resident in India or are non-resident Indians (NRI) and carry an Indian passport. India offers an Overseas Citizen of India (OCI) status.

An OCI is not a full citizen (they hold a foreign passport but may have been born in India or have Indian heritage), but they possess a smart card granting them a lifelong right to visit, live, and work in India.

Taxation: India’s taxes are based on residency, not citizenship. If you live outside India, you are not taxed on your global income. There is no confusion about “permanent homes.”

Property Rights: OCI holders can buy residential and commercial property. They are only restricted from buying agricultural land (though they can inherit it).

Ease of Access: An OCI card acts like permanent residency, no visa renewals, no police reporting, and the ability to work in the private sector. When you compare the clarity of the Indian model with the confusion of the Ugandan model, it is clear that Uganda needs to go back to the drawing board.

For Ugandans in the diaspora to view their homeland as a viable destination for foreign direct investment, they need confidence in their legal status and property rights. The URA’s current zeal is likely to have unexpected consequences.

Rather than persuading the diaspora to invest, they may force a sell-off of assets to avoid the risks of a system that seems intent on penalizing its own people. It is time for a policy review that recognizes the diaspora not just as a cash cow, but as partners who need legal protection, clarity, and respect.

The writer is based in Australia.