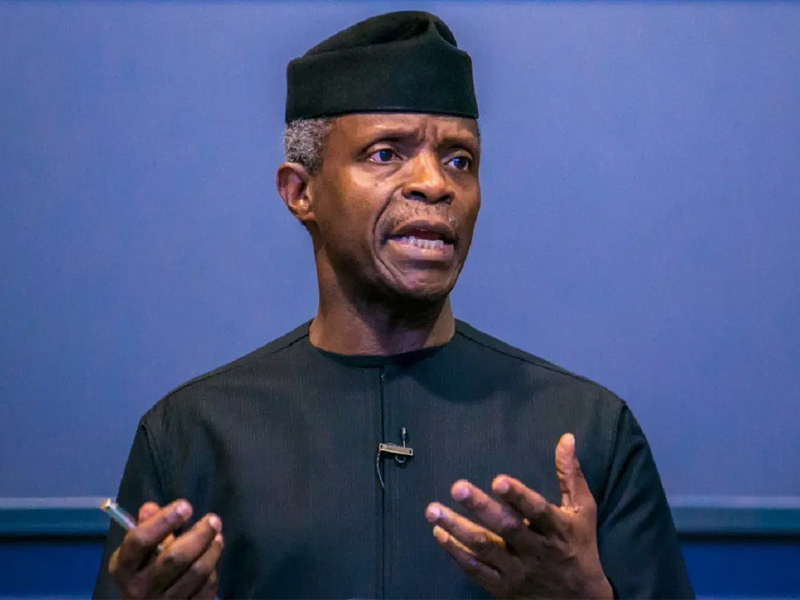

Former Vice President, Professor Yemi Osinbajo, on Tuesday, made a strong case for return to deliberate, state-led planning and infrastructure-driven development as the pathway to inclusive housing and sustainable urban growth in Nigeria, particularly in the South-west.

Osinbajo spoke at Wemabod Limited’s Real Estate Outlook 2026 held at the Grand Ballroom of Oriental Hotel, Victoria Island, Lagos, with the theme, “Unlocking Land and Infrastructure for Inclusive Housing: A Regional Agenda for Sustainable Urban Growth.”

Drawing extensively from the historic Bodija Estate development in Ibadan, Osinbajo said the project was not an accident of growth but a product of intentional planning embedded in a broader regional development programme that included free education, civil service expansion, and economic planning.

He said the demand for housing in Bodija was anticipated, planned for, and shaped, rather than being a reaction to population pressure.

Osinbajo explained that Bodija was conceived as a complete neighbourhood, not merely a collection of houses. It followed a clear planning hierarchy, enforced setbacks and plot ratios, maintained low-rise density, and incorporated green buffers and open spaces, he stated.

He said the estate prioritised profitability alongside accommodation, privacy and integration, and was strategically located close to employment centres, services, and institutions rather than being pushed to the urban fringe.

Osinbajo said that reduced commuting distances and firmly anchored the estate within the economic and social life of the city, allowing Ibadan to grow around it rather than away from it.

He said, perhaps, Bodija’s most radical achievement was its deliberate social mix. The estate accommodated modest bungalows for lower-income households, semi-detached units for middle-income earners, and larger homes for senior professionals, without segregation.

“Teachers lived near civil servants, skilled workers shared streets with professionals. Social integration was designed, not accidental,” he said.

Equally important, according to Osinbajo, was the infrastructure-first approach adopted in Bodija. Roads, drainage, water supply, electricity, schools and community facilities were delivered before occupation.

Infrastructure was treated as a public good, not a private burden, quietly subsidising affordability by reducing the cost of living for residents who did not have to self-provide basic services.

He described infrastructure as the hidden foundation of affordable housing, stating that when households bear the burden of water, access roads and flood protection, affordability collapses.

However, the former vice president lamented that the failure of Bodija lay not in its design but in its non-replication across the South-west.

Osinbajo stated that if governments in the region had delivered similar large-scale, mixed-income estates every decade, from the 1960s, the South-west would today have a network of inclusive neighbourhoods with shorter commuting distances, lower transport costs, and stronger social cohesion.

He also pointed out that Bodija’s planning principles inadvertently addressed sustainability long before climate change became a global concern.

Its compact, low-rise density, building orientation, tree cover and proximity to jobs reduced energy demand and flood risk. More than 60 years later, its layout and land values remain resilient, despite infrastructure deterioration caused by densification, commercialisation and decades of underinvestment common to many government-owned estates.

Contrasting Bodija with contemporary housing developments, Osinbajo stated that fiscal stress, structural adjustment, and rapid urbanisation from the late 1980s pushed governments out of direct housing delivery, leaving private developers and public-private partnerships to fill the gap.

He said the shift resulted in gated, homogeneous estates targeted at narrow income brackets, often located on urban fringes far from employment centres and poorly served by public transport.

The consequences, he said, included longer commute times, higher transport costs, lost productivity, rising carbon emissions and urban sprawl.

Osinbajo said infrastructure in many cases had been privatised at the household level, increasing housing costs and accelerating physical deterioration.

He said socially, many well-built estates excluded low- and middle-income households by design, pricing, and location.

While acknowledging that modern private estates got many things right, particularly the rediscovery of the infrastructure-first principle, Osinbajo said they remained expensive precisely because infrastructure costs were internalised and capitalised into house prices, making inclusion structurally impossible.

The fundamental difference between Bodija and contemporary estates, he stressed, was institutional and ideological. Bodija followed a clear sequence: planning first, infrastructure next, housing last he said.

It benefited from public land assembly, unified planning authority, and socialised infrastructure costs borne by government.

Modern estates, by contrast, institutionalised exclusion through pricing, location, and gating, he stated.

Osinbajo said land and infrastructure remained the two binding constraints to inclusive housing.

He said land scarcity was institutional rather than physical, driven by fragmented ownership, speculative land banking, high transaction costs, and weak coordination.

Similarly, housing affordability was tied to the cost of living, not just construction.

He proposed properly planned public-private partnerships in which governments provided land, bulk infrastructure, fast-track approvals, and enforced inclusionary zoning, while private developers brought capital and execution capacity.

Inclusionary zoning, he said, must be mandatory in large estates to ensure a consistent supply of affordable and social housing.

He also called on states to act as land assemblers and master planners, enhance housing finance to match real incomes, include informal workers through flexible repayment systems and digitise land records to reduce disputes and delays.

Rejecting the notion that governments could not provide housing, Osinbajo cited Borno State, which built nearly 15,000 housing units in three and a half years, despite limited revenue.

According to him, inclusive housing is achievable if there is political will.

“It is entirely possible,” he said. “It is a matter of priority and political will.”

Bennett Oghifo