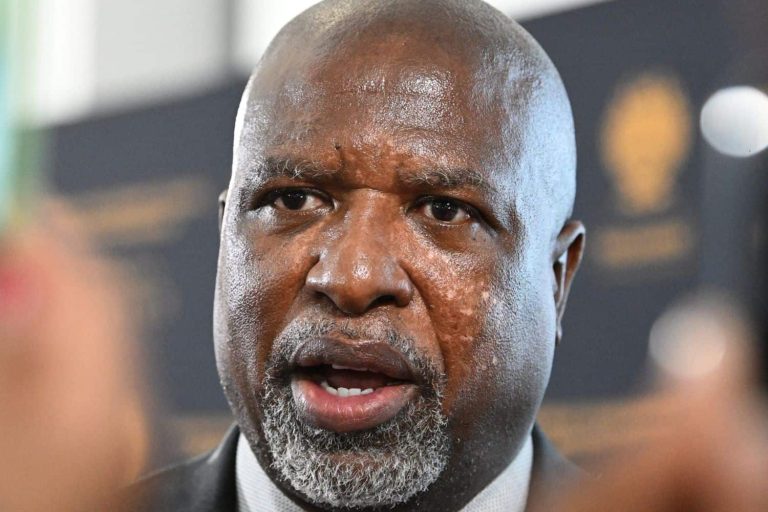

Energy expert Nick Agule has said that “Nigeria is the worst when it comes to energy poverty in the whole world,” blaming decades of poor policy choices, weak regulation and undercapitalised operators for the country’s persistent electricity crisis.

Speaking in an interview with ARISE NEWS on Wednesday regarding Nigeria’s power sector reforms, Agule argued that the flawed privatisation of electricity assets under former President Goodluck Jonathan in 2013 laid the foundation for the current problems. According to him, while the government moved to privatise power generation and distribution companies, it failed to properly reform or fund the transmission segment, creating a major bottleneck in the electricity value chain.

He said, “President Jonathan, in 2013, privatised the electricity sector, but he did it in a very bad way, and that’s what is causing this problem. What did he do? He privatised the generating companies and privatised the distribution companies, but he did not do anything with the transmission company. Initially, they gave it to Manitoba in Canada, and then they took it back into government coffers.

“So, that transmission bottleneck is because the government does not have money to modernise and expand the transmission capacity. And then it comes to the distribution company in Abuja. The disco licenses were awarded to companies that have no known history in the power sector. They have no experience, they have no managerial capacity, they have no technical capacity, they have no financial capacity. They scrambled for these licenses, and they don’t have the money to invest. How can they be waiting to take money from tariffs to invest? Nobody does that. How much have the operators in the power sector put in? They haven’t put in anything, and Nigerians are just being strangulated.”

To underscore the depth of the crisis, Agule revealed that he pays significantly more for electricity in Abuja than he does in London, despite enjoying uninterrupted power supply in the UK.

“I pay for electricity in the United Kingdom, where I have a home. I pay for electricity in Nigeria, where I have a home. I’m paying far more for electricity in Abuja than I pay in London, and yet in London, I get 24/7/365 electricity non-stop.”

He said Nigeria’s energy poverty is stark when compared with other countries. While the United Arab Emirates, with a population of about 12 million, generates roughly 45,000 megawatts of electricity daily, Nigeria’s 200 million-plus population struggles to put about 5,000 megawatts on the grid.

“It is so poor that this economy cannot lift off the ground,” he said, linking the electricity deficit to Nigeria’s modest national budget of about $40 billion. By contrast, he noted that Brazil, with a similar population size, operates a budget of around $1.2 trillion.

He further noted, “The entry cost for electricity is much higher than telecoms, but so is the tariff. The tariff for electricity is much higher than telecoms. So you put in more money in the electricity, you get more money out.

“So, you are saying that the entry cost is high, and that is exactly the problem. The problem is that people who have these licenses in the electricity sector in Nigeria don’t have the capital to pay for this entry cost. But if you give it to competent, well-resourced operators, they will bring in the billions of dollars that are needed, and they will build this infrastructure with this high entry cost, and they will deliver electricity to Nigerians, even at a fraction of the current cost. Why are they being allowed to sit on these licenses when they don’t have the money to pay for this entry cost? That is the question.”

Melissa Enoch