In little more than a decade, the design of global finance has undergone a quiet revolution.

According to The Global Findex Database 2025: Connectivity and Financial Inclusion in the Digital Economy, financial access has expanded at a pace once thought improbable, powered largely by the mobile phone.

From Kampala to New Delhi and São Paulo, the tools of economic participation are increasingly digital. Yet while access has widened dramatically, resilience and financial well-being remain stubbornly uneven.

The report paints a picture of remarkable structural progress, tempered by enduring inequalities and new digital risks. Uganda sits inside one of the most dramatic financial transformations of the past decade.

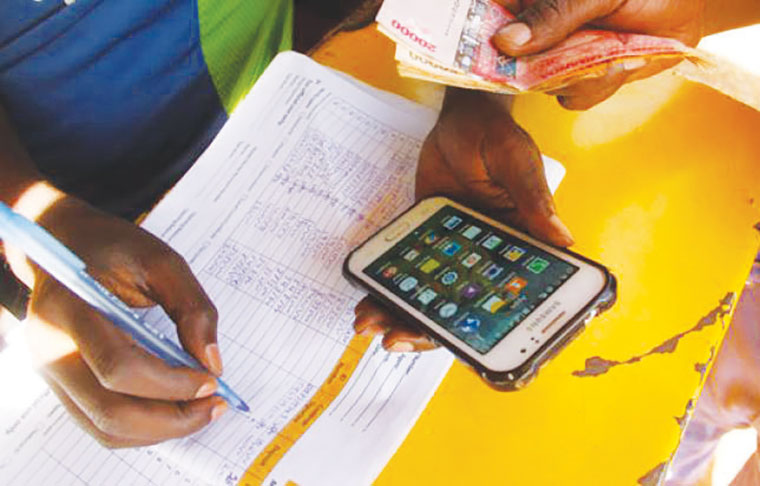

The penetration of the mobile phone in Uganda has revolutionized financial inclusion. In small trading centres, a shopkeeper simply taps his or her phone to confirm payment for sugar and soap. The money moves instantly. No bank slip. No queue. No paper trail.

Just a vibration and a message: transaction successful. This is the new face of finance in Uganda. According to the World Bank’s Global Findex 2025, across Sub-Saharan Africa, mobile money accounts now reach 40 per cent of adults, up sharply from just three years ago.

Globally, “nearly 79 per cent of adults have a financial account, a leap powered not by bank branches, but by mobile phones.”

For Uganda, where telecom-led innovation turned basic handsets into pocket-sized banks, the numbers feel familiar. Digital payments are now routine. Government transfers arrive electronically. Market traders save in mobile wallets.

Young entrepreneurs build businesses on transaction histories that did not exist a decade ago. But beneath the digital glow lies a harder truth, according to the report. Access has expanded. Resilience has not.

More than half of adults in low- and middle-income countries still cannot cover two months of expenses if income stops.

“Only 56 per cent can access emergency funds within 30 days. Digital payments are booming, but formal credit lags behind. Savings accounts exist, but many do not earn interest. Fraud is rising. Digital literacy remains uneven.”

And the poorest Ugandans are still the most likely to remain excluded from smartphones, broadband andadvanced financial tools. The infrastructure revolution has happened. The well-being revolution has not.

Uganda now stands at a crossroads familiar to much of Africa: how to convert mobile money dominance into genuine financial security.

“The next chapter of inclusion will not be about opening accounts. It will be about building stability in a country where droughts, job losses and price shocks test households daily.”

The mobile phone has changed how money moves. The question now is whether it can change how families survive. The Findex report confirms that digital payments have become the most widely used formal financial service in low- and middle-income countries.

Sixty-one per cent of adults made or received a digital payment in 2024. Forty-two per cent made digital merchant payments, up sharply from 35 per cent in 2021. Three-quarters of government payment recipients now receive funds digitally. In places like Kenya and Uganda, digital retail payments have become routine.

For small businesses, this creates transaction histories, a digital footprint that can, in theory, unlock access to formal credit. For governments, it reduces leakage in social programs.

For consumers, it means fewer hours in bank queues. But access does not automatically equal security. The Findex data reveal a more complicated reality beneath the celebration. Only 56 per cent of adults in low- and middle-income countries say they could access emergency funds within 30 days.

Half could not cover two months of expenses if their income stopped. Despite the surge in digital accounts, overall financial resilience has barely shifted since 2021. In Uganda, where floods, droughts, and rising food prices regularly strain households, that statistic lands heavily.

A boda-boda rider may accept digital payments all day, but if his motorcycle breaks down, he may still rely on friends or informal lenders to survive the week. The report highlights another tension: “digital payments are spreading faster than digital credit. While about a quarter of adults in low- and middle-income countries borrowed formally in the past year, 35 per cent relied on informal sources. Payments are digitizing rapidly; credit markets are not keeping pace.”

Saving behavior, however, has changed significantly. Forty per cent of adults in low- and middle-income economies saved formally in 2024, a 16 percentage-point jump since 2021. In Sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America, mobile money accounts are now central to saving habits.

Digital wallets allow small, frequent deposits, lowering barriers that once kept low-income households outside formal banks. Yet only about half of those formal savers earn interest on their balances.

Many mobile wallets function more as pass-through accounts than wealth-building tools. For Uganda, this presents both an opportunity and a warning. The infrastructure for inclusion largely exists. Mobile penetration is high. Agent networks reach deep into rural areas.

Digital payments are normalized. But without stronger savings products, affordable credit, and insurance, digital inclusion risks ending at convenience rather than empowerment. The Findex report also notes encouraging progress on gender gaps. In low- and middle-income countries, “73 per cent of women now have an account, up from 50 per cent in 2014. The global gender gap in account ownership has narrowed to four percentage points.”

Still, inequalities persist. Women in these economies are nine percentage points less likely than men to own a mobile phone. More than 300 million women in South Asia alone remain without one, according to the report.

Income, even more than gender, now drives digital exclusion. Poorer adults face the largest barriers to smartphone ownership and reliable internet access. In Uganda, where smartphones remain expensive relative to average incomes, that digital divide is visible.

Basic feature phones may support mobile money, but more sophisticated financial services increasingly require internet access and apps. Even among those connected, risks are growing.

Nearly one in five phone owners globally report receiving scam messages. Only three-quarters of mobile money users use passwords to protect their phones, and in Sub-Saharan Africa, only about half do.

As digital finance expands, so does exposure to fraud, hidden fees and data misuse. For regulators in Kampala and across the region, this is the next frontier. Consumer protection frameworks, transparent fee structures, and digital literacy programs are no longer optional extras; they are central to financial stability.

The report makes clear that 1.3 billion adults worldwide remain unbanked. Yet many already possess the prerequisites for inclusion: “a mobile phone, official identification, and a SIM card registered in their name. In Sub-Saharan Africa alone, about 80 million unbanked adults meet all three criteria.”

Reaching them will be harder. The remaining unbanked are disproportionately poorer, more rural, and less digitally connected. Expanding inclusion now requires not only digital investment, but last-mile agent networks and targeted support for device affordability.

For Uganda, which has positioned itself as a regional fintech innovator, the Findex findings present a strategic pivot. The era of celebrating account numbers may be ending. The next phase is about impact. Are accounts active?

Do they help families weather shocks? Do digital payments translate into affordable loans for small traders? Can transaction data support fair lending rather than predatory pricing? The mobile phone has become the new bank branch. But a bank branch alone does not guarantee financial health.

The Global Findex 2025 shows a world transformed by digital connectivity. The revolution has reached most hands. In Uganda and across Africa, the challenge now is to ensure it strengthens households, not just transactions. Financial inclusion, it turns out, is no longer about access alone. It is about building security in an economy that fits inside a pocket.