One of South Africa’s most renowned journalists and a respected media academic, professor Anton Harber may be officially retired, but journalism remains his lifelong calling.

Even beyond the lecture halls, he continues to write, reflect and contribute to the craft that defined his career.

Semi-retirement has afforded him more time to relax, read and stay connected to the world of news.

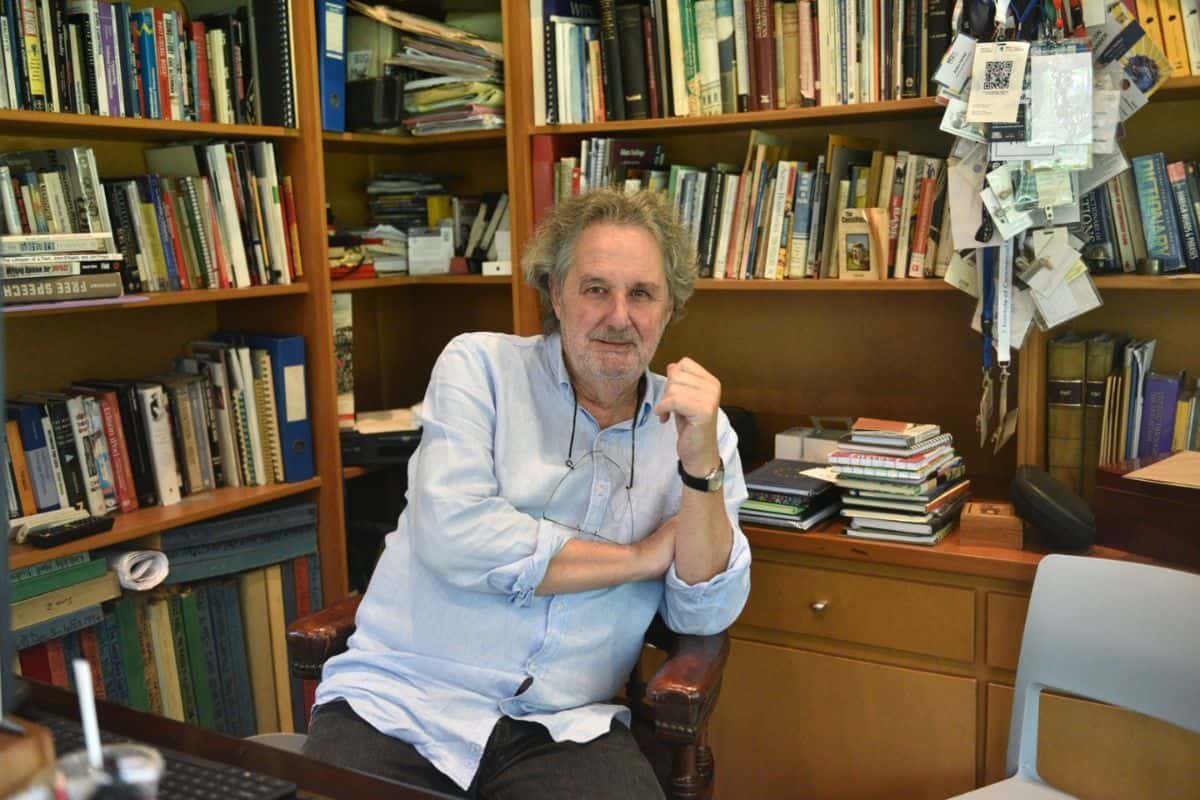

His Parkview home in Johannesburg, with its towering wall-to-wall bookshelves, is a testament to his voracious reading habit.

New arrivals spill onto the coffee table and sofa, prompting him to quip: “Look, I have no more space here.”

Photographer Nigel Sibanda, capturing the moment, teased: “Yes, we can tell you are a bookworm, professor.”

Harber’s roots trace back to Durban, where he grew up in a liberal household that shaped his progressive outlook.

With characteristic wit, he reflects on his youth: “Being from Durban means that before anything else, I am a failed surfer.”

His upbringing -son of a jazz musician father and a caterer-restaurateur mother -instilled both creativity and resilience in him.

Harber, 67, has been married to Harriet Gavshon, television and film producer (Quizzical Pictures), for 40 years and they have two adult children.

“My parents both grew up in hardship, so they taught me to value education and hard work. And a love for jazz. I cook, but since my daughter is a professional chef, these days I defer to her,” he said.

After matriculating at Carmel College, Harber pursued politics and English literature in Johannesburg, already determined to become a journalist.

He recalls teaching himself to type on a manual typewriter, “banging away on one of those pre-electric machines”.

His journey began at the Springs Advertiser, a family-owned paper where he learned the fundamentals of reporting.

He then joined the Sunday Post, working under the formidable Percy Qoboza.

Harber’s involvement in the Mwasa (Media Workers Association of SA) strike, which ultimately closed the paper, signalled the start of his radical journalism.

From there, he moved to the Sowetan as deputy chief sub-editor, contributing to its bold anti-apartheid stance, before joining the Rand Daily Mail (RDM) as a political reporter.

When the RDM was shut down in 1985, Harber and some colleagues launched The Weekly Mail, determined to create an alternative voice in a media landscape constrained by censorship.

Harber said: “We were a younger generation who saw the story had moved to the township streets, the factory floors and the exile movements. We took a more strident view in opposing apartheid, fighting censorship, and covering resistance politics.”

Co-editing the paper with Irwin Manoim, Harber faced harassment, petrol bombs and state intimidation, yet described it as the most challenging and most exhilarating period of his career.

ALSO READ: University application crisis can’t just be ‘that time of the year’, do better minister

Training the next generation

Harber has long been involved in training young journalists.

The Weekly Mail Training Project produced a new generation of editors, such as Mondli Makhanya and Ferial Haffajee.

And in 2001, Harber transitioned into academia, joining Wits University to establish its journalism programme as the Caxton Chair of Journalism.

Over 20 years, he trained a new generation of media professionals, many of whom now hold influential positions.

Though retired from Wits, he insisted: “I never stopped practising journalism. I continue to research, write columns and books, and engage with younger journalists who are entering a very different world.”

Today, Harber devotes much of his time to the Henry Nxumalo Foundation, named after the famous Drum Magazine investigative reporter, who wrote under the name of “Mr Drum”, who exposed the terrible conditions of black labourers and prisons under apartheid.

The foundation supports investigative journalism in the public interest.

“We step in when a journalist needs resources to do in-depth digging, particularly for accountability. A number of exposés over the past two decades were backed by us.”

His latest initiative, Our City News, is a virtual newsroom focused on Johannesburg that holds city management accountable in innovative ways.

Looking back, Harber paid tribute to journalists who risked their freedom during apartheid, reminding people that today’s media freedom was hard-won.

Yet he warned of new challenges: “Now, the biggest threats to journalism are financial and technological. Social media undermines much of our work, while disinformation and hate speech spread unchecked.

“Good journalists are needed more than ever to separate truth from nonsense, but it is getting harder as the search for truth is drowned out by noise.

“It is true that under financial pressure, many newsrooms have retired the more experienced and expensive journalists and filled their ranks with less experienced youngsters. Youngsters often bring a fresh perspective, so it is good to have them, too.

“But we try to bring together maturity and experience with youthful energy. It’s a great mix when one gets it right. What we really lack these days is editing – so much of the work we see appears to be raw, unverified and unedited.”

Most media outlets seem to be sidelining or avoiding hiring old journalists.

Is the old generation of journalists irrelevant today and what role can they play in today’s media environment?

“I see our role as supporting young journalists and enabling them to do their best work. There are still excellent pockets of journalism in this country and we have to keep these going,” Harber said.

Through his career as a journalist, editor and academic, Harber has remained steadfast in his belief that journalism is essential to democracy.

His legacy lies not only in the stories he told but in the generations of journalists he inspired to continue the fight for truth.

NOW READ: Teacher allegedly conned into quitting job, loses pension in R1.27m ‘ancestral investment’ scam