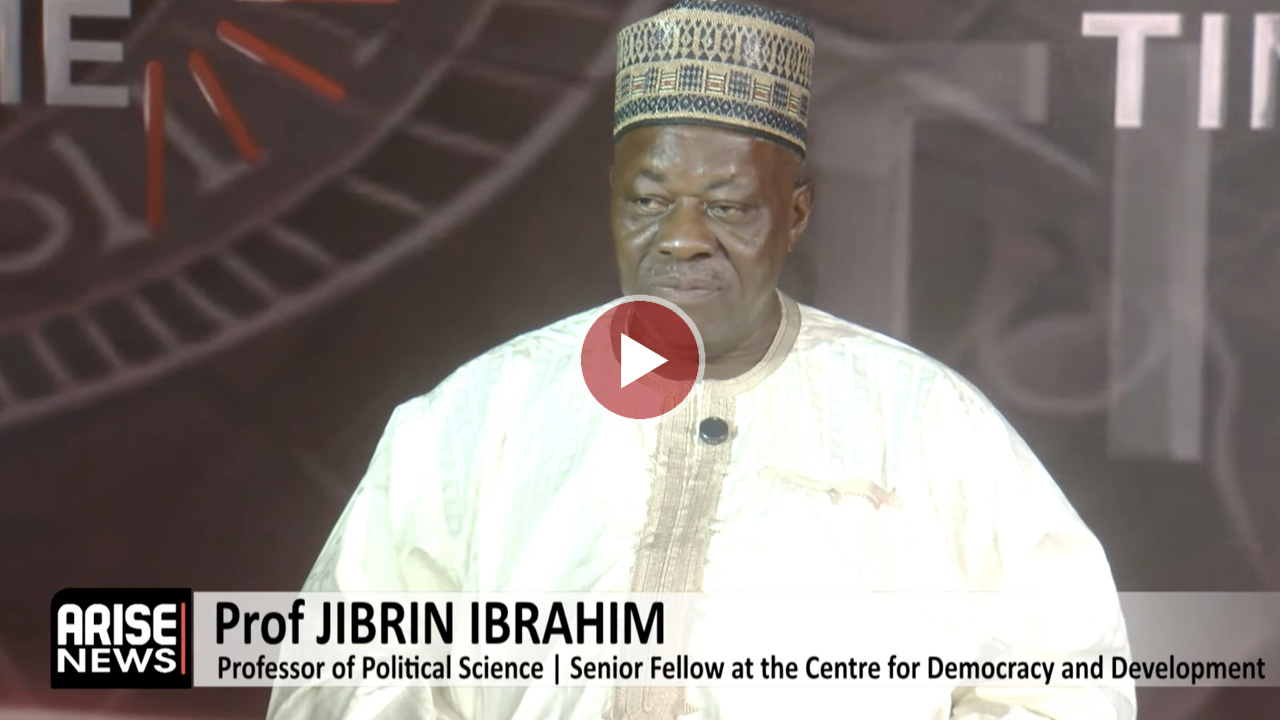

Professor of Political Science and Senior Fellow at the Centre for Democracy and Development, Prof Jibrin Ibrahim, has warned that the political class’s refusal to embrace gradual reform is pushing Nigeria towards a potentially explosive national crisis.

Speaking in an interview with ARISE News on Wednesday, Ibrahim argued that historically, significant reforms in Nigeria have only occurred at moments of major systemic shock, when the political elite believed the survival of the state was at stake.

“I think the reading you are proposing is a correct one, that significant reform has occurred in Nigeria only at moments of major shock to the system, where the entire political class feels and believes that it cannot continue as it had been doing, and that the survival of the system will require a dramatic reform,” he said.

He traced this pattern back to the January 1966 coup, noting that key demands for electoral, regional and census reforms were dismissed by the governing class, creating a political blockade.

“It’s important for people to read his speech, because that was the message of his speech, that Nigeria was not amenable to reform, that a revolution was necessary to induce profound change, and that was why they were engaged, as he put it, in a revolution, and their method, as he put it, was going to be a revolutionary method,” Ibrahim said.

He added that subsequent milestones — including the transition to the Second and Fourth Republics — also followed crises triggered by failed or manipulated electoral processes.

“The Nigerian governing classes successively have completely rejected the line of reform, even when it was clear to everybody that that was the only way to save the country. And it’s only under force that they have been ready to accept reform,” he stated.

Turning to the present, Ibrahim described Nigeria’s current situation as one of the gravest in its history, marked by deepening poverty, insecurity and democratic backsliding.

“There’s a sense in which the crisis we’re in today is one of the most serious we’ve ever had in the history of this country. First of all, we have the crisis of livelihoods. Over 65 per cent of Nigerians are living in poverty. This is higher than it was in 1960, higher than in 1990, higher than in 1980. We have more poor people in the country today than we’ve ever had in our history. And that should be really a cause for general concern,” he said.

However, he argued that poverty alone rarely produces reform.

“Mountain poverty has rarely led to reform around the world. Because people are in such a struggle for survival that this struggle is translated into their individual daily lives. They must get enough to eat today; they never think of tomorrow. And that consumes all their energy for that day. And the next day they begin again. So it doesn’t really lead to reform.”

Instead, he identified insecurity as the most substantive crisis confronting the country.

“This country has never been as insecure and as unsafe as it is today. And this is something that directly brings state responsibility into the question. Because the state, our constitution says, has a responsibility to provide for the welfare and for the security of Nigerians. With massive poverty, our welfare is not catered for. With massive insecurity, nobody is protecting Nigerians from armed banditry, insurrection, and what have you.”

He further warned of a deepening political crisis.

“Democracy is disappearing before our very eyes, where the fundamental principles are being dulled, where the National Assembly and the presidency are showing a clear commitment to disrupting multiparty democracy in the country, imposing a one-party regime, shutting up the opposition, shutting up criticism. And finally, using money to bribe all voices that try to speak. If they can’t bribe them, they put them in jail. They find excuses to do that.”

Ibrahim described the situation as “almost total crisis”, but noted that its generalised nature has muted the kind of dramatic rupture seen in the past.

He criticised what he described as a prevailing belief within the governing class.

“This belief of this government — and this is what I pick up in everyday talk — that every Nigerian has a price. If you cannot be bribed, more money can bribe you. So that’s the attitude, that they can take care of everybody who tries to resist. But that is often the case until the time when there is an explosion. Unfortunately, in social science, we never can tell when that explosion will be. We still don’t have the tools to understand what the signals are, how those signals will translate into timing in terms of the explosion.”

Warning that a major shock in a fragile state could tip into failure rather than reform, he pointed to the proliferation of arms as a troubling sign.

“The first definition of a state is that it has the monopoly of the use of arms. There are six million guns in the hands of civilians in this country. And that’s more than the guns in the hands of the agents of the Nigerian state. So already, the state is really, really extremely fragile. And that’s a clear sign of the beginning of state failure, when the state no longer has a monopoly of the means of legitimate use of violence in society.”

Distinguishing Nigeria from countries with high civilian gun ownership but strong institutions, he added: “It’s not the possession of the arms. It’s the way in which the arms are used against the law, against constituted authority. And the problem in Nigeria is that these young people with arms are using it for insurrection, are using it for kidnapping, are using it for banditry, are using it to attack people on the basis of their religious faith. They are using it in a series of illegal and unconstitutional means. And that’s why it becomes a very serious crisis.”

Asked whether steady decline or disruptive shock posed the greater danger, Ibrahim said the real threat lay in the refusal to reform.

“I think what is more dangerous is the refusal for gradual reform. We are not reforming this country. I mean, the past week, for example, is a key issue. When Nigerians have realised that the National Assembly, or the Senate in particular, is trying to compromise the electoral process to make it easier for them to rig elections, that’s the objective of their proposed reform.

“And that’s something that hurts Nigerians, that frightens Nigerians, and makes them realise they’re going to lose even the little democracy that we have because of the recklessness of a political class that wants to stay in power, irrespective of the wishes of the Nigerian citizen. By taking this attitude, they really pose the risk of precipitating the country into a major national crisis,”he concluded.

Boluwatife Enome