Electricity and Energy Minister Kgosientsho Ramokgopa disclosed on Monday (12 December) that government will have to subsidise Glencore and Samancor’s electricity costs by R5.2 billion as part of an interim plan to buy time for a sustainable solution to the high energy costs currently killing the country’s ferroalloy industry.

He was unable to specify where the money will come from but assured that “we will find it”.

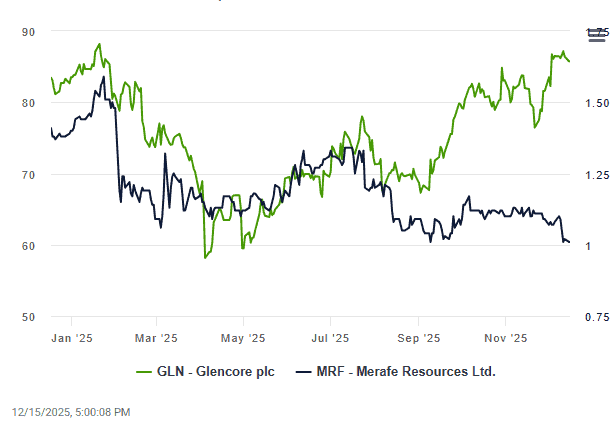

This comes after Eskom’s announcement of a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) with Samancor Chrome and the Glencore-Merafe Chrome Venture on 8 December to develop a long-term intervention before the end of February.

ALSO READ: Eskom signs deal aimed at saving SA’s shrinking smelter sector

Eskom offers relief

Ramokgopa explained that the smelters are already paying only R1.35/kWh in terms of negotiated pricing agreements (NPAs). The normal price would have been R2.12/kWh. The difference is currently being subsidised by other electricity users.

Electricity costs account for 40-60% of their total expenses, and even with the discount, they pay three to four times more for electricity than their global competitors.

Eskom was prepared to cut the price further to 87.7c/kWh, the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM), which participated in talks about the matter, revealed.

According to Ramokgopa, the “sweet spot” at which the smelters can survive is between 60c and 70c/kWh.

Glencore agreed to pause the Section 189 process it had already initiated, which would have resulted in the loss of 2 500 jobs, pending the finalisation of a long-term intervention before the end of February.

To cover the difference between the 87.7c and R1.35/kWh that the smelters are currently paying, the government must now find R5.2 billion, says Ramokgopa.

The expected job losses without the intervention will be much wider than Glencore and could amount to 300 000.

This is according to the Ferro Alloy Producers Association (Fapa).

Glencore Alloys CEO Japie Fullard says the proposed solution falls outside the tight regulatory straitjacket of the national energy regulator, Nersa. Ramokgopa, however, has certain powers that can be used to clear obstacles out of the way.

ALSO READ: Eskom finalises MoU with ferrochrome producers to save thousands of jobs

New entity

The plan involves the establishment of a central entity, a role that could possibly be fulfilled by the Industrial Development Corporation (IDC).

This entity would purchase coal at the current low, market-related prices from various South African coal mines, which are currently struggling to export their product due to oversupply. “We are creating a new market for them,” says Fullard.

The coal would then be used at some of Eskom’s older coal-fired power stations, such as Matla and Hendrina, which are underutilised or scheduled for closure. The entity would subsequently buy the electricity at a drastically reduced price of 62c/kWh and wheel it to the various smelters across the country.

“It is like an independent power producer that simply uses Eskom’s power stations to convert coal into electricity,” explains Fullard.

Fullard and Fapa have already engaged with the coal mines, and the proposal has the support of Minerals Council SA, which represents mines across the country.

He says that, apart from the state support until the end of February, the plan requires no subsidies and benefits all parties involved.

Addressing concerns that South Africa would increase its coal usage and thus its carbon footprint under such an agreement, Fapa chair Nellis Bester says this would only be temporary. “By 2028, the industry would systematically transition to renewable energy.”

He adds that many of the power stations can also be adapted to be more environmentally friendly.

He emphasises that the smelters, as electricity consumers, are also very valuable to Eskom. Their constant electricity usage, day and night, plays an important role in stabilising the national grid, especially in maintaining baseload during the night.

ALSO READ: Almighty scrap breaks out between steel rivals as ArcelorMittal winds down

Reviving several furnaces

Bester says each smelter has several furnaces. Nationwide, there are about 80 furnaces, of which only six are currently in operation.

If the plan is accepted, he believes up to 70% of them could be brought back into operation over the next few years.

“It’s phenomenal what this could do for the economy and for the country. We once again become a country that adds value to its own critical minerals and can help reduce the unemployment rate.”

Some of the products delivered by the ferroalloy industry, such as ferrochrome, ferromanganese and ferrosilicon, are key inputs in the production of steel and stainless steel, which in turn are used in manufacturing and construction – all major job creators that have declined sharply in recent times and in some cases have come to a standstill.

Fullard also points to about 30 anthracite mines that are currently idle but could return to operation if the plan succeeds.

ALSO READ: Glencore-Merafe retrenchments are another casualty of Eskom

Regulatory challenges

Making the plan a reality within the limited time available will, however, not be easy, says Deon Conradie, an electricity tariff expert and former general manager for electricity pricing at Eskom.

Conradie confirms that Eskom’s tariffs must, by law, be cost-reflective and that the utility may not discriminate against any customer or group of customers.

To implement the proposed solution, a commercial mechanism will therefore have to be devised.

While he is positive about the new approach, he points to several regulatory realities that will have to be managed:

- Nersa/tariff rules: Any off-tariff arrangements that effectively change the price to a retail customer risk regulatory scrutiny. It must be ensured that there is no breach of licence conditions or requirement to seek Nersa approval.

- Competition law: Preferential deals could be examined by the Competition Commission for abuse of dominance, exclusionary conduct, or anti-competitive tying.

- Public procurement/state-owned entity rules: As Eskom is a state-owned enterprise, its procurement processes and related discounts must comply with legislation, Treasury regulations, and internal governance.

- Transparency and auditability: To withstand scrutiny, contracts must be auditable and include open-book mechanisms, independent pricing benchmarks, and anti-avoidance clauses.

- Fiscal/state aid concerns: If a government subsidy is involved, it must be budgeted and defensible as part of industrial policy.

This article was republished from Moneyweb. Read the original here.