At 6:40pm in Nakapelimoru village, the sun sinks behind the hills, staining the sky orange.

In a small manyatta, 17-year-old Peter Lomilo crouches over a pot of boiling leaves—ekorete—because there is no food. His younger siblings hover around him, dizzy with hunger. School ended for them two years ago; the family could not afford even the “free” education costs.

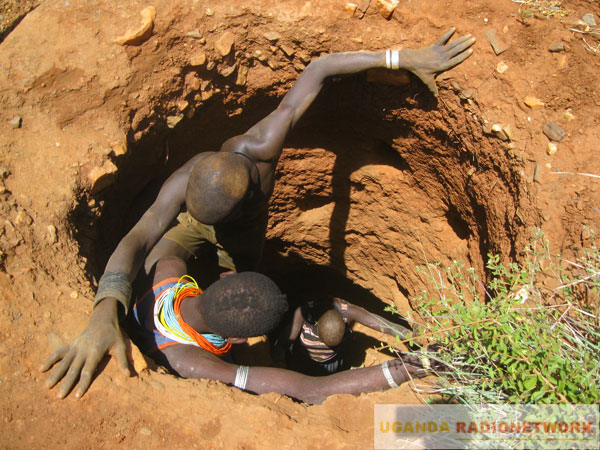

This is Karamoja in 2025—a sub-region that has absorbed billions in government programmes, donor funds and NGO attention. Yet today, people still boil wild leaves for dinner, youth roam trading centres searching for nonexistent jobs, and districts rank at the bottom of nearly every human development indicator in Uganda.

Against this grim backdrop, President Yoweri Museveni’s fresh capital promises ahead of the 2026 elections—including special funds for youth skilling, iron sheets re-distribution schemes and a revitalized wealth creation agenda—have been received with cautious hope and deep skepticism.

In Nakapelimoru, Lonrengechora and Rupa, the question is whispered in manyattas and sung in youth circles: “If the pledges are fulfilled, why does poverty still live with us? Karamoja has endured decades of government interventions, donor programmes, food relief cycles and countless strategic frameworks.

Billions of shillings have been poured into the sub-region. Yet it remains the poorest place in Uganda, with chronic hunger, low literacy, weak markets, limited livelihood security and persistent cattle theft that cycles between criminality and survival.

This is the story of a broken and fractured area. Karamoja has heard promises before. It has also been forgotten before.

BUT WHY KARAMOJA?

Karamoja’s development trajectory has long been shaped by two competing paradigms. (1) The security lens. Since the 1970s and 1980s, government policy has primarily framed Karamoja as a security problem, focusing on disarmament, cattle rustling and military operations.

This approach, though necessary at times, has dominated development planning, often sidelining livelihoods and social services. The humanitarian lens. Decades of drought, famine cycles and humanitarian aid have entrenched a relief-oriented economy.

The region has more NGO warehouses than functional factories, and food aid remains a routine expectation rather than an emergency measure. From the Karamoja Integrated Development Plan (KIDP) to Operation Wealth Creation (OWC) and most recently the Parish Development Model (PDM), each initiative came with large budgets and political fanfare.

Yet the outcomes on the ground remain depressingly similar: lowest literacy rates in Uganda, highest levels of malnutrition and stunting, chronic food insecurity, minimal private sector activity, poor infrastructure and near- zero industrialization.

WHAT YOUTH, WOMEN AND LOCAL LEADERS SAY

“I finished Senior Six in 2021,” says 19-year-old Caral Apalorot, from Moroto. “My classmates in Kampala are working or at university. For me, the only job I got was carrying sand for Shs 5,000 a day.”

Her dream is to become a nurse, but the district’s scholarship program collapsed years ago. In Nabilatuk, Narenge, a mother of six, sits beside a dry seasonal riverbed.

“Every election season, they come with promises—tractors, goats, money for women groups. After elections, we never see them again,” she says. A senior district planner in Kaabong admits that allocations often arrive late—if at all.

“We submit budgets, but releases are unpredictable. Last year, our agricultural extension officer positions remained unfunded while the region received thousands of kilograms of seeds without proper planning.” Elders argue that development programs ignore pastoralist identity.

“They want us to farm, but they don’t give us water or irrigation. They want us to settle, but they provide no services,” says an elder from Tepeth.

THE POLICY BOTTLENECKS

Karamoja’s planning has been dominated by security agencies rather than economists, agriculturalists or community planners.

This has resulted into reactive rather than long-term interventions and prioritization of peacekeeping over production, and has generated mistrust between communities and the state.

Different ministries run overlapping projects; Ministry of Karamoja Affairs, Ministry of Gender (for youth funds), Ministry of Agriculture, OPM humanitarian wing, OWC, PDM, UWEP… No central coordination. No unified development strategy.

Poor coordination among stakeholders, including government bodies, NGOs and development partners, has been a persistent challenge for development initiatives in Karamoja.

This has led to issues such as service replication, inefficient resource allocation, limited community consultation and lack of unified strategy for addressing the sub-regions complex challenges. The ministry of Karamoja Affairs is designated as the main coordinating body, but it requires sufficient staffing and skills to work effectively with the diverse range of international partners.

Without this capacity, development partners may be less committed to a centralized approach.

POOR INFRASTRUCTURE AND MARKET ISOLATION

Roads linking Moroto, Kotido and Kaabong remain patchy. Electricity coverage is minimal. Such isolation means: high transport costs, no industry, and low investor confidence. This is definitely a sub-region stuck in the same storyline.

As Uganda goes through the charged 2026 election season, Karamoja is once again at the center of renewed political interest. Presidential convoys return, government officials inspect long-forgotten projects, and pledges of capital injections echo across trading centres.

It is a familiar sound: promises of tractors, restocking livestock, modern markets, valley dams, youth skilling centres and mineral wealth-sharing programmes. Yet on the ground, nothing feels new.

Indeed, this is a fractured story, of a sub-region where development rises during election years but collapses once the ballot boxes leave. Karamoja’s development narrative is tightly interwoven with Uganda’s election cycles.

Every five years, the sub-region becomes a stage for political symbolism. New wealth-creation initiatives are launched hurriedly, funds are pledged, and previous failed interventions are rebranded as fresh solutions.

In 2025 alone, the sub-region has been promised 10,000 youth supported under capital skilling schemes, livestock restocking under renewed OPM programmes, solar-powered valley dams and irrigation models, support to revive the collapsed cattle economy, and increased sharing of mineral revenues with host communities.

These promises mirror those of 2021, 2016 and 2011. Some are copies of pledges made in the late 1990s under the Karamoja Integrated Disarmament and Development Programme. Each cycle raises hope—and disappointment.

Local leaders argue that election-year interventions are often politically timed, short- term, and lack follow-through. Once campaigns end, the pace slows. Funds dry up. Projects stall. Contractors vanish.

The result is a pattern of “start-stop development” that leaves Karamoja locked in the same struggles. In sharp contrast to the year in, year out promises, the 2023/2024 National Household Survey report by Uganda Bureau of Statistics (Ubos) captured Karamoja’s poverty rate as dire; at 74.2 percent, which is four times more than the national average, and despite a national decline in poverty to 16.1 percent.

The same Ubos report said an estimated 84 percent of the youth in Karamoja were experiencing multi-dimensional poverty. While the United Nations Development Programme in 2023 noted that economic regression, food insecurity, women and youth unemployment and inequality, all resulted in the loss of lives and livelihoods in the sub-region.

Ambrose Toolit, the executive director of Grassroots Alliance for Rural Development (GARD), told URN in a previous interview, that although poverty and underdevelopment in Karamoja have been attributed to conflict, the sub-region has since experienced relative peace, but poverty levels remain high.

He estimated that Karamoja had received up to one trillion shillings from international development donor partners through the central government, local government, UN, international NGOs and local NGOs in the last ten years.

“But in real development terms, it’s difficult to point to or put a figure to this money,” he concludes.

Johanes Mbabazi, of the Advocates Coalition for Development and Environment (ACODE), is of the same view. He, however, admits, that on realizing this challenge as civil society, they have intervened and are trying to get stakeholders to account for the resources they invest in the sub-region.

The coordinator of Restless Development Uganda, Henry Napokol agrees that the resources injected in the sub-region have not positively impacted the communities. He attributes thissituation to lack of accountability.

“The people do not understand the activities and investments offered for their transformation.”

The chairperson of the Elders Association, Simon Nangiro, wondered why several accountability bodies have been assessing the project implementations but failed to track how the resources are being spent.

The minister of Karamoja Affairs, Simon Peter Lokeris, on the other hand, remains confident about the progress in Karamoja. In an interview with the news agency URN, he said that the region is gradually transforming through the collaborative efforts of government and development partners.

The 2016 Donor Mapping report compiled by the then USAID-supported Karamoja Resilience Support Unit (KRSU) comprising 10 donors including USA, World Bank, Irish Aid, SIDA (Sweden), EU, Germany, Japan KOICA (Korea) and Italy, provided a significant majority of the external funds flow to Karamoja.

MISSED OPPORTUNITIES

Karamoja is a climate hotspot. Yet, no substantial irrigation investments exist, grazing corridors remain unplanned, drought resilience programs are underfunded and education is collapsing under teacher absenteeism, classroom shortages, early marriages and hunger pushing pupils out of school.

Health services remain inadequate with frequent stock-outs and understaffing. Karamoja’s comparative advantage is livestock—yet policy favours crop agriculture despite erratic rainfall.

A modern livestock value chain (dairy, meat processing, hides and skins) would transform the area—but there is no robust investment. Gold, marble, limestone and rare earth minerals are abundant. But communities gain almost nothing, as illegal and exploitative mining persists with no transparent revenue-sharing model in sight.

A 2021 story Ubuntu Times, an online publication, titled, “Mining Rush Threatens Indigenous Peoples in Karamoja Uganda” points out a series of challenges from land grabbing, impact on the environment to challenges on indigenous rights.

The report said in spite of billions of investments into mining projects that arguable injected new life to the sub-region in form of jobs, in the same vein it has brought new problems threatening livelihoods of millions of Karimojong people.

“In a region long inhabited traditionally by cattle keepers, the rush to get the regions precious minerals (gold, limestone and marble) is uprooting people, damaging key water sources, and stirring social unrest. Local talk of being displaced from their ancestral farmlands by land grabbers while others are now suffering from many diseases, including skin infections and diarrhea, blamed on consuming water from contaminated sources, as some miners use hazardours chemicals including mercury to extract gold.”

With stunning landscapes, unique culture, and proximity to Kidepo Valley national park, Karamoja could be a tourism hub. However, lack of infrastructure and branding keeps tourists away.

Young people run small shops, boda businesses, carpentry, solar repair, and crafts—but lack capital, training or market access. The presidential promise of “Karamoja youth industrial hubs” has yet to materialize beyond speeches.

The author is a fellow of defence and security group Kings College London