permits, backed by pilot processing hubs. Image: Chris Ratcliffe/Bloomberg

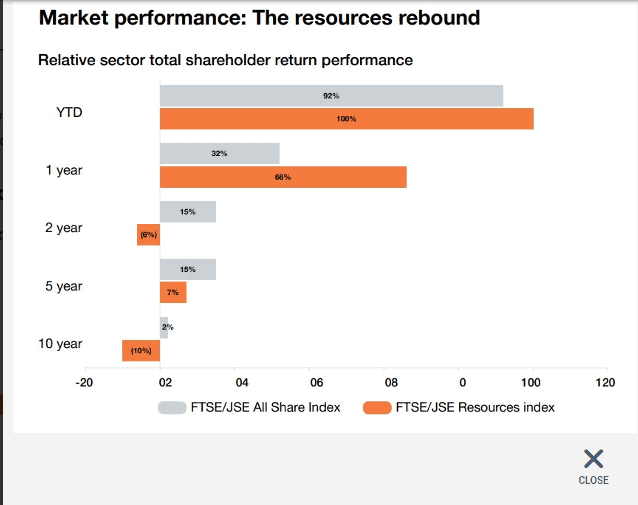

Once-unloved gold has been the standout performer in the mining sector – reaching 48 new highs over the year to June 2025 – says the latest PwC Mine 2025 report released this week.

On Tuesday evening, gold surpassed another historic high of $4 000 an ounce, soaring well clear of the average $2 300/oz recorded in 2024.

Sticky inflation and geopolitical tensions (including Trump tariffs and the US shutdown) kept gold’s safe haven status alive, while large-scale central bank buying – particularly in China, India and Turkey – cemented a floor under prices.

SA’s gold mining sector has profited handsomely from rising prices but suffers from declining production, says PwC.

The country has fallen from the world’s top gold producer to around 10th place today due to ageing deep-level mines and operational challenges, not least of which are power shortages and seismic events, which kept volumes relatively flat.

“Elevated gold prices offset stagnant output, leading to improved financial performance for gold mining companies,” says the report.

For platinum group metals (PGMs), 2025 was a story of two phases: prices remained under pressure in the first quarter, prompting cost-cutting and retrenchments, followed by a sharp price rebound in the second quarter to levels not seen in a decade.

ALSO READ: Why the sudden shine in gold again?

SA accounts for roughly 70% of global platinum supply, 35% of palladium, and nearly 100% of rhodium and iridium.

What happens in SA has a powerful effect on global PGM dynamics.

There’s been some recalibration of battery demand for electric vehicles, with surging hybrid vehicle sales providing support for demand for auto catalysts using PGM material.

SA PGM producers were forced to cut output and restructure operations, creating a global supply shortage.

The World Platinum Investment Council forecasts the global supply to decline by 4% in 2025, which will lead to upwards pressure on prices.

ALSO READ: JSE breaches 107 000 for first time as gold stocks shine

Coal

Coal is another stalwart in the SA commodity mix, with demand hovering near record levels at home and abroad. Coal prices have declined from their 2022 peaks but remain elevated compared to historic levels.

Some 80% of SA’s power still comes from coal, but rail and port bottlenecks have forced miners to prioritise Eskom offtake. Domestic coal production is projected to increase by about 3% to 247 million tonnes (Mt) – supported by new initiatives such as Seriti’s Naude Bank Colliery and MC Mining’s Makhado hard coking coal project.

Transnet’s coal line ran at 62% capacity during the year, which had a negative impact on exports.

Government has shortlisted 11 private operators in the hope these will expand capacity by about 20Mt in the coming year. This should also lift exports by roughly 10Mt from the 2023 low of 47Mt.

Iron ore

China’s property downturn, and an aggressive US trade policy, has impacted demand for iron ore, while local steelmakers struggle with a roughly 800% increase in power costs over the last decade, logistics frictions, and imported competition.

In April 2025, SA iron ore exports to the US were flagged for a proposed 30% tariff, while ArcelorMittal SA says it will close its long-steel operations, potentially impacting 3 500 jobs.

ALSO READ: Gold and platinum shares steal the show as JSE cracks new high

Other minerals

SA has the potential to produce world-class manganese, alongside decent volumes of vanadium, nickel and rare earth elements.

The deposits are there and a pilot lithium project is underway at Blesberg in the Northern Cape, but there are gaping structural impediments: a backlog in exploration; a slow licensing process; limited capacity for battery-grade production; and a shortage of skills in some sectors.

The government’s Critical Minerals Strategy aims to bridge these gaps by prioritising geoscience investment, faster permitting, local beneficiation, and by enabling infrastructure such as power and logistics.

Mining houses executed fewer but bigger deals over the last year.

- Harmony is set to acquire MAC Copper in Australia, adding copper to its gold portfolio;

- Exxaro will acquire stakes in Ntsimbintle/OMH manganese assets;

- Anglo American sold off 51% of its platinum interests under the new name Valterra, while also offloading nickel and coal interests in Australia and Brazil;

- Sibanye-Stillwater plans to dispose of its Beatrix 4 shaft for around R500 million; and

- South32 will acquire 19% of American Eagle Gold to help build out its copper portfolio.

Gold Fields is planning to lock up 100% control of its Canadian Osisko Mining asset, alongside an Au$3.7 billion buyout of Gold Road Resources in Australia.

AngloGold Ashanti will acquire 83.6% control of Centamin for $2.5 billion; its main asset is the Sukari Gold Mine in Egypt.

What will it take to win in 2026?

The main bottlenecks are rail and ports. It will take unblocking these arteries, getting private operators onto the rail lines, securing rail corridors, and restoring predictable slotting for coal, iron ore and manganese, says PwC.

The energy bottleneck is also choking expansion. SA needs to accelerate private generation and energy wheeling, while stabilising tariffs and prioritising grid access for self-generation.

Government can do its part by converting the Critical Minerals Strategy into faster permits, backed by pilot processing hubs and facilitating financing.

ALSO READ: Global mining sector revenue fell by 3% in 2024, but gold revenues increased 15%

Illegal mining

Another area where government can play a role is in clamping down on illegal mining, much of it happening at the roughly 6 000 abandoned mines in SA.

This is reckoned to cost the country R60 billion a year.

It started with gold and diamonds, but illegal miners have since moved to other commodities such as copper, chrome and coal.

Getting on top of illegal mining will require collaboration between government, communities and the private sector.

This article was republished from Moneyweb. Read the original here.