In the time it takes to boil a kettle, President Ramaphosa had finished the few sentences he delivered on gender-based violence and femicide (GBVF) at the 2026 State of the Nation Address (Sona).

To the survivors waiting for help, those 72 seconds felt less like a plan and more like treating an official disaster as a footnote.

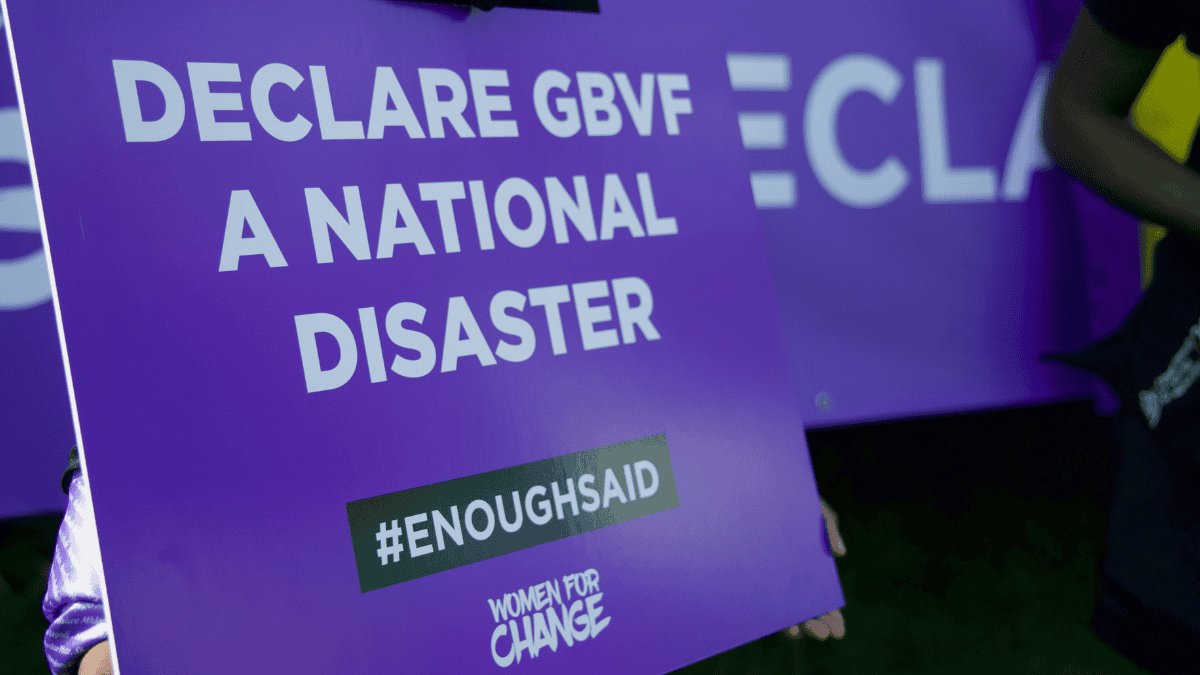

GBVF was officially declared a national disaster on 20 November 2025, mobilised by over a million voices.

Such a declaration was supposed to be the turning point.

A national disaster, usually, demands a nation’s full attention (and its chequebook).

Yet, the crickets on funding allocations, timelines, and concrete interventions were loud at the Sona.

Has the urgency in treating GBVF as an immediate national emergency evaporated?

ALSO READ: GBVF officially classified a national disaster in South Africa

Why is everyone still waiting for action?

Civil society group Women for Change operations and advocacy manager, Merlize Jogiat, told The Citizen that since the GBVF classification, the government has declared two other disasters.

Namely, floods and rains in several provinces, and the foot-and-mouth disease (FMD).

Both came with timelines, implementation strategies, and budget allocations.

GBVF, meanwhile, is three months into its “disaster” status and remains a ghost while body counts still rise.

Though Ramaphosa highlighted the National Council on GBVF (NCGBVF), the expansion of sexual offences courts, and new shelters, he recycled the hits: “mobilising sectors,” “economic empowerment,” and “faster investigations.”

These are “long-standing promises repeated in previous SONA addresses, predating the National Disaster classification,” Jogiat said with frustration.

The speech failed to name who will oversee the work. It also offered no strategy for the public to track the money or see real results.

Women for Change argues that the country cannot truly prosper while its women and children are in danger.

They believe that economic growth means nothing if the people aren’t safe.

“The government has used political will in all other avenues. Why is this the one area they refuse to use political will?” wrestled Jogiat.

ALSO READ: A shame SA has world’s highest levels of violence against women and girls, Ramaphosa says

Why is the National Council still not selected?

Once the NCGBVF is appointed, it will lead the country’s fight against GBVF by ensuring the National Strategic Plan (NSP) is implemented.

The NSP serves as the essential roadmap to end the crisis of violence against women, children, and the LGBTQIA+ community.

The Parliamentary Legal Services Office launched an investigation into the selection process of candidates for the NCGBVF. This came after formal complaints from Lawyers for Human Rights, Corruption Watch, COSATU, and We Will Speak Out SA, who warned that several shortlisted candidates weren’t actually qualified for the role.

Highlighting the gravity of these failures, Jogiat remarked: “The selection of the council [was] actually appalling.”

On Tuesday, 17 February, Parliament was given an update on the process, which has stalled while Parliamentary Protection Services wait for state security agents to complete vetting of the applicants.

Women, Youth and Persons with Disabilities Portfolio Committee member Tshehofatso Meagan Chauke-Adonis expressed frustration with the timeline, noting that vetting delays have forced the committee to postpone the final shortlisting.

The government expects to adopt its final report of recommended candidates for the NCGBVF by 24 February 2026.

ALSO READ: South Africa can end GBV now

Exclusion olympics

Jogiat says that the selection of the council should include those who have worked in the GBV space before.

But, “it’s clear that civil society was never contacted or even brought into that conversation.”

“The truth of the matter is, although we, in my opinion,… are the custodians of what the classification implementation should look like, we are not being treated as such.”

She says they tried to reach out to the DWYPD and the South African Minister of Cooperative Governance and Traditional Affairs (CoGTA), but neither department has responded.

Jogiat warns, “This classification is going to be handled like every other thing to cover up bad behaviour.”

“Embarrassment is what the government wants to avoid above everything else.”

Jogiat says that the bigger problem is that both CoGTA and the DWYPD appear to be operating in isolation. They aren’t talking to each other about what implementation should actually look like.

“In a true national disaster response, red tape is removed so that political will can take over, ensuring everyone is within the same communication lines.”

She says instead, the current structures appear to be more hurdles than solutions, bogged down by excessive signing powers and a revolving door of meetings that prioritise adding new complaints over establishing a clear strategic direction.

The Citizen is still awaiting comments from both departments.

Supporting survivors

Despite this, Women for Change continues to create solutions.

They plan to launch a WhatsApp line in a couple of weeks to reach the unreached communities to report on crime.

“We don’t have operational funding,” Jogiat reveals, but “we know what these people need.”

“A disaster response cannot be measured in speeches; it must be measured in lives saved,” added founder Sabrina Walter.

NOW READ: ‘Government’s systems have failed us’: Women For Change vow to not stop