Screenshot

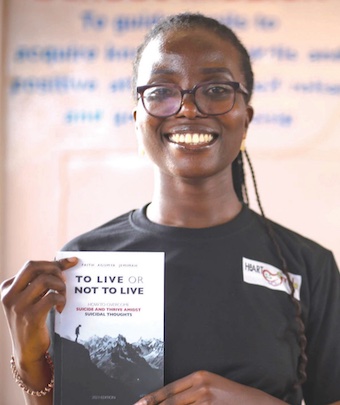

FAITH AGUMYA is a lawyer and an award-winning mental health advocate with a leadership through lived experience in the mental health space.

She is the founder of Kwa Imani Community, a youth-centered organization that focuses on suicide prevention and mental health awareness through dialogue and the arts. Quick Talk caught up with her at Endiiro, Kamwokya for a chat.

Please tell Quick Talk briefly about yourself.

Agumya Faith is a suicide-prevention advocate. She is also a lawyer by profession. And she leads an organization called Kwa Imani Community, which specializes in suicide prevention among young people from ages nine to 23 years.

How do you do that?

We do it through creativity and the arts to build resilience. Through that, we create a mind that is accustomed to coping in healthy ways rather than coping in all these other things that we end up getting addicted to, like drugs and alcohol.

You also had mental health challenges?

It’s in the recovery journey that you start to unpack what led you to struggle in a certain way. All these problems started way back in primary school when my dad decided to switch me to an international school, and I struggled to fit in.

Much as I didn’t come from a humble background, kids in school were better off than me. They made fun of my dad’s car for being so small, made fun of my bald hairstyle, and started calling me names; this really affected my self esteem and mental health.

How does a child handle that?

I did twice as much. I got involved in almost every school activity so as to attract friends. I started pressuring my parents to do certain things for me, such as buying me a princess bag and pink stuff like the kids at school and many other things. Honestly, not that I really wanted them, but I just wanted to fit in.

When did it become a problem?

I had just joined secondary when my dad passed away. It was a hard time for me, and I became really isolated. I had few friends, yet I was in desperate need of company.

The problem kept growing, and I became accustomed to being the way everyone else was. And before that, I had a problem of figuring out who I was, what my identity was, what my preferences were.

So, it got to a point that I would just do whatever, anything that would help me be seen or have a group of people around me.

When did all this turn into suicidal thoughts?

The suicidal thoughts started in primary school. I would write things down such as “I’m tired of living”, “I don’t want to live anymore.” Then it escalated to cutting myself.

I would use the divider to draw things on myself, to draw the things that would annoy me. In secondary, it escalated to burning myself, to smoking, and all those things to try and numb the emptiness I felt. It went on like that until at university when I ended up on a surgery table.

What led you to a surgery table?

I went through a period of severe physical and emotional distress that affected my health and eventually required surgery. The lead surgeon of my case is the one who notified me that I was struggling with mental health issues.

I had never heard of it. So, he was like, “I will not tell your mom, but you have to consent to help. If you don’t consent to help, I’ll tell her what just happened.” He helped me get the help and seek medical attention, and I started seeing a psychotherapist.

Did your parents know any of this?

My parents were both working parents; really, really busy. I remember my dad noticing in primary that I had changed when I started asking for everything.

That’s when he asked me what was going on at school. I think that was the only time. I think we were all busy. Or maybe they knew and didn’t tell me. I don’t know.

How was your healing journey?

It wasn’t easy. I was faithful for the time I was in rehabilitation for the surgery; that time where the doctors tell you, “You can’t move, you can’t do this, you can’t do that until the scar is healed.”

I was only faithful in the start because I knew I was seeing my surgeon often. He was holding me accountable. When the rehabilitation got finished around eight months after, I went back to being a workaholic and living unhealthy habits.

I was now uncomfortable being around my friends. How do I tell my friends, “Hey, I’ve been diagnosed with a mental illness”? I

was not willing to unpack with anyone. So, I lived in isolation for a really long while. I even stopped medication. But I’m glad that I’m where I am now.

Going back a little bit, what did the psychotherapist diagnose?

I was diagnosed with clinical depression and generalized anxiety disorder. To me, it was more like a silent battle. I didn’t know that it was a problem. I thought that it was just a character trait.

How did you turn your struggles into a journey to inspire others?

I began with writing my first book in 2023 called To Live or Not to Live. I always wrote things like poems, journals and articles. However, I was writing very dark things. But during my healing journey, I lost a very close friend to suicide.

Both of us had been self-harming, and I thought I would go before him. His death really broke me. The pain I went through and his family was so much, and that was my actual turning point. I was like, I don’t wish this kind of pain on anyone, no matter what they’ve done.

Never knowing answers, never having a last conversation or whatever conversations with this person. That’s how the book came. I share signs and symptoms and ways people can get help and things people can look out for that are unusual.

Could you tell Quick Talk about Kwa Imani Community?

I had planned to just sell the book. But then I started getting phone calls and stories of young people having similar struggles.

I just knew I had to speak up and be more intentional about creating a community of people like me and helping one another through ways that helped me. That’s how Kwa Imani came about.

How does that work – dealing with mental health through art?

Now, like today, we had a session at a certain school in Mukono. We encourage young people to express what a safe space means to them through different art forms and we pin them after so that the whole school would be reminded of what a safe space means and looks like for the students.

It can be a song or poem or even a painting, and we have sold some of these paintings, and they have got money. So, instead of isolating, smoking, and other harmful things, we teach them to divert that time into something positive.

In the future, we want to do theater productions and all sorts of things about mental health. It has really been therapeutic, and it has built resilience as well among the young people we deal with.

What are some of the most common mental health issues you have observed among young people?

I’ve noticed most of the young people are dealing with addiction. There are people who can’t sleep without watching porn. And young people become addicted.

They don’t even act on it. They don’t masturbate, but they watch it and then get some sleep. Young people are actively looking for ways to not feel the bad things that have happened to them.

What can be done for people to be free to talk about their struggles?

It starts with an individual. If you are at your home and you can’t talk to even just your sister or your brother, how are you going to be open to strangers? I believe the only way we can help and curb this issue is starting from as far as homes.

I like how, you know how the Aids campaign is? Who doesn’t know? Like, everyone knows about Aids even people in the village. So, one of the things I would appeal for is mainstreaming mental health.

Confidently talking about it on TV, on billboards, every place.

Lastly, how is your life outside mental health advocacy?

Well, I work seven days a week. But I love everything that I do. On the side, I train models to be exceptional young women. I run a pageant where we train models to be more than queens.

But I love the fact that I’m doing everything that I love. I don’t joke about ministry. I don’t play about my faith as well. So, it’s church activities, work…

devonssuubi@gmail.com