Things are looking better for South Africa. The tide has turned.

This, the view of Adi Enthoven, one of the country’s business elite, has resonated across a country worn down by years of economic and social decline.

Enthoven is no lightweight. He’s the third-generation heir of a formidable business dynasty, but, more importantly, he has long championed the corporate sector’s growing involvement in government delivery.

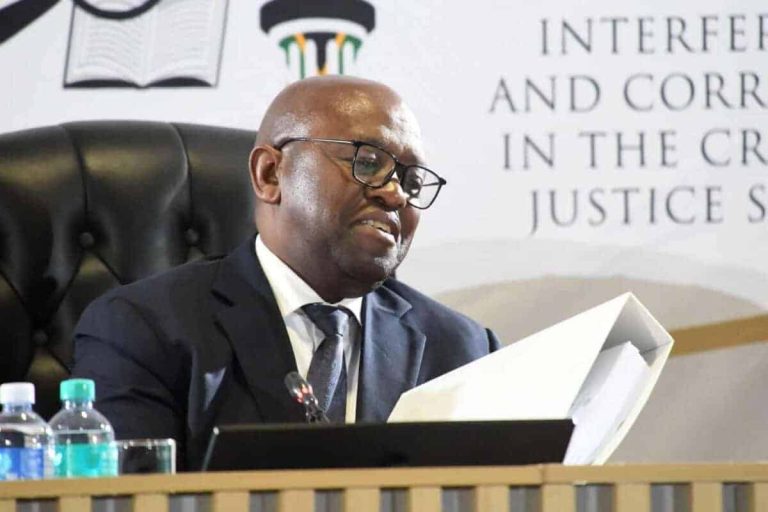

As board member of Business Leadership South Africa (BLSA) he’s been at the gear-grinding interface of BLSA’s partnership with government, which for two and a half years has seen about 20 CEOs work almost daily with departments, and with Enthoven himself heading the energy cluster.

This is what has inspired his optimism. Enthoven sums up the dominant South African narrative as being one of “failure and decay”, with many accepting that a failed state is inevitable.

“They have long lost hope,” he says, “giving rise to an unfortunate paradox: this very absence of hope actively accelerates the decline, locking us into a negative spiral.” But if South Africa has put the worst behind it and this is recognised by investors, it will fire a “powerful virtuous cycle”. He argues that, indeed, “our decline has been arrested, our trajectory is once again positive and this fact is of profound significance for our future”.

Tracing a decade of decline, starting in 2014, Enthoven notes: “Looking at the data at the end of 2023, it was hard to find a silver lining.” However, there had been an inflexion point in 2019 with the economic reforms set in motion by then finance minister Tito Mboweni.

ALSO READ: Standard & Poor upgrades SA’s credit rating for first time in two decades

The enormous infrastructural programmes proposed by the ANC government required the inspanning of the private sector through Operation Vulindlela. The result, he says, was the transformation of hitherto closed sectors into “fully open and competitive systems … This was truly revolutionary”.

While SA’s trajectory has changed, Enthoven acknowledges “the flywheel is not yet spinning” as it struggles to overcome its past inertia.

“However, when the flywheel starts spinning, confidence, growth, state finances, service delivery, job creation and national prosperity will become a self-sustaining positive feedback loop.”

This is lovely, upbeat stuff and much needed.

One hesitates to pour cold water on such admirable optimism. But while optimism deserves applause, credulity does not.

Enthoven’s lecture celebrates the technocratic repair work now paying dividends in energy, logistics and water. Yet it glides past the political economy that keeps breaking the machinery.

The political factors in the ANC that make our problems intractable cannot be ignored. The party mouths reformist intentions – stability, investment, delivery – while clinging to race-based economics and a foreign-policy posture hostile to the West and the US in particular.

These contradictions sabotage recovery. Big business are second fiddles in this performance. The state will welcome corporate help, then rebrand the outcomes as ANC achievements. Business and the GNU will fix potholes, keep lights on and trains moving, while Luthuli House claims political credit and keeps the ideological scaffolding intact.

ALSO READ: ‘Their loss’: Ramaphosa says US snub won’t stop G20 summit

In the same week that President Donald Trump announced that the US would boycott the G20 summit, Deputy President Paul Mashatile was unambiguous.

“The ANC is pro-expropriation of land without compensation, we have never deviated from that,” he told parliament.

Hope is necessary, but delusion is fatal. Mashatile’s hymn to expropriation is the dominant beat in South Africa’s governing culture.

Unless CEOs find the courage to alter the score, Enthoven’s joyful aria will be drowned out in a cacophonous finale.